home | about | blog | comments | Border Reivers |Brothers Of The Sand |Kingdom Series | Oathsworn Series

home | about | blog | comments | Border Reivers |Brothers Of The Sand |Kingdom Series | Oathsworn Series

The game of Hnefatafl (nef-uh-ta-fal)

Since it plays a significant part in Crowbone, I thought it best to show why it is so important. Popularly, the name is translated to mean 'the king's table'. Actually, it means no such thing - the word 'tafl' does derive from the Norse word for table, but, 'hnefa' is the Norse (or Old Icelandic) verb meaning to grasp, as in a fist). The verb implies both surrounding and firmly holding, which is the essence of the game. Interestingly, it might also reflect the character of society in the north, internecine relationships and why there never was a Northern Empire to rival the Roman one. In the Roman game of Chess, for example, pieces are moved outward to attack, always expanding; in tafl they are moved inward.

Still, the Roman connection is strong – Hnefatafl may be related to Ludus Latrunculorum, the Game of Soldiers, called Latrunculi for short and possibly the origin of the well-used phrase 'eff this for a game of soldiers' when real life is not following the rules. In the same era, the Persian game of Nard seems identical to Latrunculi, though it should not be confused with the unrelated medieval Nard, which is essentially Backgammon and a different beast entirely.

Late medieval writings mention various games played on boards and among those we have Brannan-Tafl, Hala-Tafl, Hnefa-Tafl, Hnot-Tafl, Hræ_-Tafl, Kvatru-Tafl and Skak-Tafl. Essentially, the games are all pretty much the same.

Hnefatafl declined in the 11th century, thanks to chess. It disappeared from Wales in the late 15th century and from Lappland two hundred years later – but we have a 17th century Swede to thank for recording the rules and board for it just before it vanished forever. Young botanist Linnaeus, travelling through Lappland classifying plants, became fascinated with the game and recorded it all in his diary.

Confused yet? You will be – we haven't started on the rules, which were always unclear and may have varied depending on where you played it!

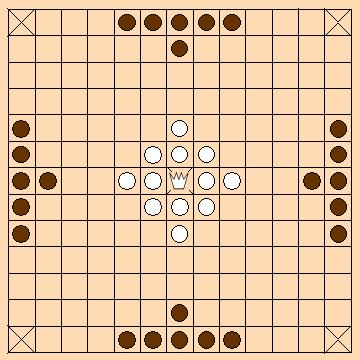

The board

It is now more or less established that Hnefatafl and its numerous variants were played on odd-sized boards as small as 7 x 7 and as large as 19 x 19. They could be wooden and ornate and might just as easily be scratched out on the dirt and played with pebbles. A beautiful carved board with 13x13 squares was found at Gokstad in Norway, a double-sided affair which has Nine Men's Morris carved on the reverse.

It is now more or less established that Hnefatafl and its numerous variants were played on odd-sized boards as small as 7 x 7 and as large as 19 x 19. They could be wooden and ornate and might just as easily be scratched out on the dirt and played with pebbles. A beautiful carved board with 13x13 squares was found at Gokstad in Norway, a double-sided affair which has Nine Men's Morris carved on the reverse.

Most boards had the starting positions – the central King's square and the corner escape squares – carved in and, in some cases, the board is drawn Go-style, the pieces standing at the intersections of the lines rather than at middle of squares (the version I prefer).

Pieces

The chief piece was called Hnefi (King) and the others were known as Hunns (lumps or knobs) – much more evocative of their expendability than even Pawn in Chess. For 9x9 boards, sixteen dark pieces surrounded eight light pieces with an additional King. Boards with more squares typically had twelve light pieces and a King facing twenty-four dark pieces. The colours were often switched.

Setup

The King (large white piece) goes on the central square, surrounded by his men (other white pieces). The enemy (black) pieces are set up around the edges of the board. Black usually moves first though this can also vary depending on players and location.

Gameplay

Played in alternate turns, all pieces move in the same way like modern rooks at Chess. You slide a single piece any number of squares in either orthogonal direction (up-down or left-right, no diagonal moves) as long as it doesn't jump over another piece of either colour. The Throne and the four corner squares are off-limits to all pieces except the King. With the smaller board variants, pieces of both sides may pass over the Throne; with the larger board variants, only the King may do so.

The object, for the White player, is to have his King escape his assailants by reaching a corner square. If the White player moves so that his King ends up with a clear path to any of the four corner squares, he must announce that he has an escape route open. If there is more than one, he announces 'doubled'. On his next turn, if he can still do so, the King may be moved to a corner square and escape. White then wins.

The object of the Black player is NOT to kill the King, but to surround and capture him. The King must be sandwiched along both axes to be captured. The Throne, corners and edges count as Black pieces for purposes of sandwiching the King, so Black needs only three pieces to capture the King on the edge of the board or if he is right beside his Throne, two if the King is right beside a corner square. When the King is in danger of being captured on Black's next move, he must announce "Watch your King" to the White player. Black wins by capturing the King, who can also be imprisoned if he and no more than one defender are surrounded on all sides and incapable of moving.

Winner

The winner is the White player if he manages to reach a corner square with his King, the Black player if he manages to capture the King. Because the game is uneven, it is good etiquette to play two games, switching sides. Each player keeps track of how many pieces he lost or took from his opponent and this score is used to determine the ultimate winner.

Variants

On smaller boards the pieces can only move one square at a time. With larger boards, the King is allowed to escape by simply reaching any edge square rather than a corner square. Optionally, a piece may not move to place itself in sandwich between two opposing pieces without being captured. Another variant, known as Brandubh by the Irish, was played with dice. A roll would either indicate the maximum distance a piece could move or whether the player could move at all – move on an odd roll, miss a turn on an even roll. But real Hnefatafl players scorn the dice version as requiring no skill at all.

There are Scottish and Irish variants, the former called Ard-Ri (The High King) and the latter Fidchell or Fithcheall, which is mentioned in the Mabinogion. Both used a 7x7 board, with slightly different starting layouts. Tablut, the Finnish variant recorded by Linnaeus (and generally used as Hnefatafl), was played on a 9x9 board. Again, all the set-ups are essentially the same as what we now call Hnefatafl.

Old English referred to the King as Cyningstan, meaning King-Stone. As an indication of perceived historical enemies, The 17th century Lapps call their Tablut pieces 'Swedes' and 'Muscovites.'

Strategy

There are many and varied ways of approaching the game. The King's forces usually possess a slight advantage, despite being outnumbered, because all the White player has to do is arrange for the King to escape the board. Some strategies claim the King player should try to capture as many attackers as possible to clear an escape route, while not trying too hard to protect his own men since they, too, can block the King's escape. The attacker's object is not only to prevent the King's escape, but also to capture him. The best way for the Black player to win is to avoid making captures early in the game, instead scattering the attackers to block possible escape routes.

At least, that's the theory – but, as observed frequently in Crowbone, the game is played more easily on a table than in life...